“I started out as a political science major but switched fields because I really love working with Alzheimer's and dementia patients. I’ve always found it so interesting. I remember one Alzheimer patient from those early years, a little lady with blonde hair and the biggest blue eyes you’ve ever seen. She came up to me one day and said, ‘Something’s wrong with me, but I don’t know what it is.’ And she started crying. I said, ‘You know, there’s something wrong with me too.’ That made her laugh. Yes, they’re sick and they need help, but they’re just like you and me. They’re still people, they can have a great quality of life, and you can learn so much from them. They’re so honest. Their filter is down, so they don’t have the ability to lie to you or give you this song and dance. They’re going to give it to you straight.

“My grandmother had Alzheimer’s, and the first time she didn’t recognize me, I just broke down and cried. She raised me as a little girl, and when she called me by my mom’s name---she had never done that---I knew something was wrong. Even though I had been in the field for many years by that time, when it’s YOUR family, YOUR grandmother, it’s like, Wow, how do you deal with that? I had to accept it, but it was so hard. She was still Grandma, and I could still have a great relationship with her, but I had to accept her where she was. She had taken care of us, and now it was our turn to take care of her.

“Alzheimer's patients may have no recollection of having children. If you ask them how old they are, they may say 23, 24, or 25 because that’s where their mind goes with the disease. When they talk about going home, they’re not talking about the home where they raised their family. They mean the home they grew up in as a child. They’ll ask where their mom or dad is. They may not recognize themselves in a mirror either. That's why we don't have any here, because they'll look in a mirror, see this old lady and they’re like, ‘Who is this? I’m 23 years old.’

“We work with families to help them understand what’s happening, how to accept the changes in their loved one, and how to deal with the day-to-day challenges. One thing we tell them is, Let Mom do as much as she can do by herself. If she can still get herself dressed, then let her do it. So what if she has her clothes on backward or inside out? Who cares? You have to pick your battles. There are more bad days than good days, but to me, the good days always outweigh the bad. We may have a whole week of Mom using the bathroom on herself, not knowing who we are, and not wanting to take her medication, but that one day or those couple of hours when she is lucid and can remember something make it all worthwhile.

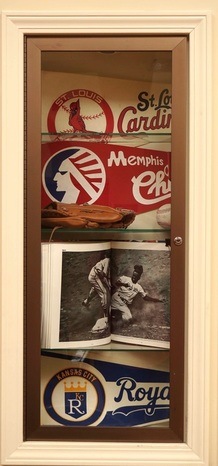

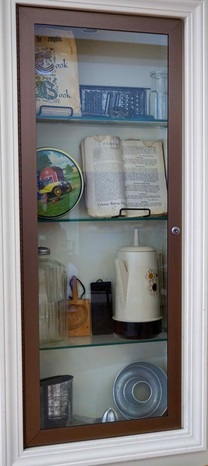

“The atmosphere here is like a community center. We encourage our friends, as we call them, to participate in conversation, music, art, games, exercise, and field trips. We encourage them to walk and feed themselves as long as they’re able. One friend rolls silverware into napkins, sets the lunch table, and pours water and juice every day. She thinks of it as her job, and it really does help us out. She even calls in if she's not coming to 'the school' that day. Like anybody else, she wants to feel needed and useful.

“I think being in this field has helped me to be more patient and more compassionate. You never know when you may be in the position of having Alzheimer’s or dementia and need someone to be compassionate and loving toward you. You wouldn’t want someone to call you crazy or make you feel bad about something you don’t even recognize is wrong with you. Working with the elderly has been my passion since I was 19 years old. I love it.”

“My grandmother had Alzheimer’s, and the first time she didn’t recognize me, I just broke down and cried. She raised me as a little girl, and when she called me by my mom’s name---she had never done that---I knew something was wrong. Even though I had been in the field for many years by that time, when it’s YOUR family, YOUR grandmother, it’s like, Wow, how do you deal with that? I had to accept it, but it was so hard. She was still Grandma, and I could still have a great relationship with her, but I had to accept her where she was. She had taken care of us, and now it was our turn to take care of her.

“Alzheimer's patients may have no recollection of having children. If you ask them how old they are, they may say 23, 24, or 25 because that’s where their mind goes with the disease. When they talk about going home, they’re not talking about the home where they raised their family. They mean the home they grew up in as a child. They’ll ask where their mom or dad is. They may not recognize themselves in a mirror either. That's why we don't have any here, because they'll look in a mirror, see this old lady and they’re like, ‘Who is this? I’m 23 years old.’

“We work with families to help them understand what’s happening, how to accept the changes in their loved one, and how to deal with the day-to-day challenges. One thing we tell them is, Let Mom do as much as she can do by herself. If she can still get herself dressed, then let her do it. So what if she has her clothes on backward or inside out? Who cares? You have to pick your battles. There are more bad days than good days, but to me, the good days always outweigh the bad. We may have a whole week of Mom using the bathroom on herself, not knowing who we are, and not wanting to take her medication, but that one day or those couple of hours when she is lucid and can remember something make it all worthwhile.

“The atmosphere here is like a community center. We encourage our friends, as we call them, to participate in conversation, music, art, games, exercise, and field trips. We encourage them to walk and feed themselves as long as they’re able. One friend rolls silverware into napkins, sets the lunch table, and pours water and juice every day. She thinks of it as her job, and it really does help us out. She even calls in if she's not coming to 'the school' that day. Like anybody else, she wants to feel needed and useful.

“I think being in this field has helped me to be more patient and more compassionate. You never know when you may be in the position of having Alzheimer’s or dementia and need someone to be compassionate and loving toward you. You wouldn’t want someone to call you crazy or make you feel bad about something you don’t even recognize is wrong with you. Working with the elderly has been my passion since I was 19 years old. I love it.”

Conversation starters:

Napkins (with silverware) rolled and ready for lunchtime:

Sara Thompson, Site / Program Coordinator

Website: Alzheimer's Day Services of Memphis, Inc. (non-profit organization)

FB: Alzheimer's Day Services of Memphis

Related article from Purple Elephant: 16 Things I Would Want, If I Got Dementia

Website: Alzheimer's Day Services of Memphis, Inc. (non-profit organization)

FB: Alzheimer's Day Services of Memphis

Related article from Purple Elephant: 16 Things I Would Want, If I Got Dementia

RSS Feed

RSS Feed