“Passing stories on was a real focal point for our family: the elders sitting with all of us, the aunts and uncles, everyone telling stories---not just at Sunday dinner or on holidays but anytime we were together. Both my parents were really wonderful storytellers. My father was older when he had us (already in his 40’s), and I don’t know what it is, but maybe when you’re older, those stories become more important, you know? You have more history behind you, and you want to share that with your children. There was one story in particular that had a big impact on me. It was about my grandfather, my father’s father. When he decided to leave China to come to the United States in 1895, he had to find some way to let his mother know. He was in Canton City, and his mother was back in their home village. My grandfather was illiterate, so he looked around for an educated man to write a letter to let her know he was on his way to the United States (or ‘Gold Mountain’ as they called it) and that he would probably never see her again. Back then you could tell who was educated and who wasn’t by the way they dressed, so he found an educated man who agreed to write the letter, but the man said, ‘We’re in the middle of the street and I have nothing to write on.’ My grandfather said, ‘Use my back.’ Years later, my grandfather told my father that when this educated man was using his back to write on, that it seemed like a thousand years had passed because he felt so humiliated. His ignorance and illiteracy had placed him in a position of powerlessness. He had become this inanimate object to be used by an educated man. My grandfather told that story to motivate his children to get an education, my father in turn told that story to us, and I passed it down to my own children.

“I was the first of my family to graduate from college, let alone earn an advanced degree, and when I finished my M.F.A. at Clemson, both my mother and my father came up for the weekend. I’ll never forget the reception at the home of the department chair, John Acorn, who is this really wonderful human being. He and my father were sitting next to each other on the porch that night, and my father told him that story, the story of my grandfather offering his back to be written on. The burden that my father had from his father, feeling helpless and humiliated by being illiterate, came all the way from Canton Province, China to the porch of John Acorn’s house in Pendleton, South Carolina. And my father, this WWII Marine Corps veteran, this soldier who was at Guadalcanal and at Tarawa, the two bloodiest battles of the war, wept as he told it. To see him relieving himself of this burden, of this family humiliation, and sharing it and being vulnerable was an incredibly raw moment. I saw the power of that story with him, his need to share it, his need to feel a sense of accomplishment and to fulfill an obligation to his own father. It was a powerful force that I’m sure couldn’t contain itself.

"My father died in 1990, a month after I got my first full-time tenure-track job. He was such a warm, kind, well-loved, well-respected man, not only in our family but also in the larger community. When he died, it was the first time I ever felt like I was truly alone. Intellectually I understood that my parents would not be around forever---it’s an unavoidable thing---but the psychological and emotional reality of it, I never had a taste of until then. I'll have his stories forever though, and I'll continue to pass them down. They're very, very important to me. Those stories have played a big part in shaping who I am.”

“I was the first of my family to graduate from college, let alone earn an advanced degree, and when I finished my M.F.A. at Clemson, both my mother and my father came up for the weekend. I’ll never forget the reception at the home of the department chair, John Acorn, who is this really wonderful human being. He and my father were sitting next to each other on the porch that night, and my father told him that story, the story of my grandfather offering his back to be written on. The burden that my father had from his father, feeling helpless and humiliated by being illiterate, came all the way from Canton Province, China to the porch of John Acorn’s house in Pendleton, South Carolina. And my father, this WWII Marine Corps veteran, this soldier who was at Guadalcanal and at Tarawa, the two bloodiest battles of the war, wept as he told it. To see him relieving himself of this burden, of this family humiliation, and sharing it and being vulnerable was an incredibly raw moment. I saw the power of that story with him, his need to share it, his need to feel a sense of accomplishment and to fulfill an obligation to his own father. It was a powerful force that I’m sure couldn’t contain itself.

"My father died in 1990, a month after I got my first full-time tenure-track job. He was such a warm, kind, well-loved, well-respected man, not only in our family but also in the larger community. When he died, it was the first time I ever felt like I was truly alone. Intellectually I understood that my parents would not be around forever---it’s an unavoidable thing---but the psychological and emotional reality of it, I never had a taste of until then. I'll have his stories forever though, and I'll continue to pass them down. They're very, very important to me. Those stories have played a big part in shaping who I am.”

Richard A. Lou, Professor and Chair of Art Department, University of Memphis

- Stories on My Back Exhibition at Crosstown Arts (article)

- Stories on My Back Exhibition at Crosstown Arts (Commercial Appeal article)

- Stories on My Back Exhibition at Texas Tech University (article)

- Border Consciousness and Artivist Aesthetics: Performance and Multimedia Artwork (article from American Studies Journal)

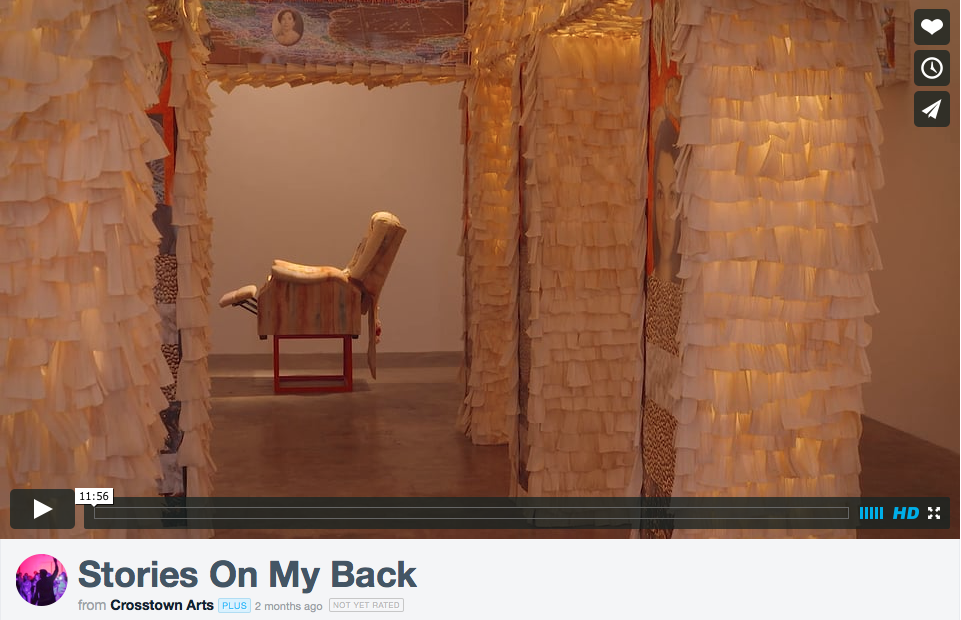

From the Stories on My Back exhibition at Crosstown Arts (video):

On the Shore of the East China Sea, a story Richard's father told (narrated by Richard's children):

RSS Feed

RSS Feed